At the cinema with Hergé

When the young Georges Remi went to the cinema, what films were wowing audiences in Brussels? Let's find out!

Real adventure

First let's set the scene. Hergé was born on 22 May 1907 (this year a big birthday party is being organised at the Hergé Museum to celebrate the occasion). The cinema, as we know it today, was born in 1895. You read all about it in our previous report Secrets of the Cinema! Contrary to what some people claim, Hergé was not an avid cinemagoer in his adult life. His second wide couldn't remember going to the cinema with him once. 'In the same way he almost never read comic strips,' she also explained. Hergé often said, 'I am like a sponge and there is a risk that all kinds of episodes, exploits and gags could get lodged in my memory. When they come to the surface years from now, I will probably think that they are memories of my own life!' He felt the same way about cinema. The mental formation of the imagination of the young Hergé was nourished by cinema among many other things. But he was also influenced by what he read at school. All the same Hergé preferred stories of real life that he gleaned from newspapers, to the novels and adventure stories that made up the literature he read as a child. When he growing up his imagination took off and memories of his youth made way for an overflowing of adventure and gags, which filled an entire 24 books!

War and cinema...

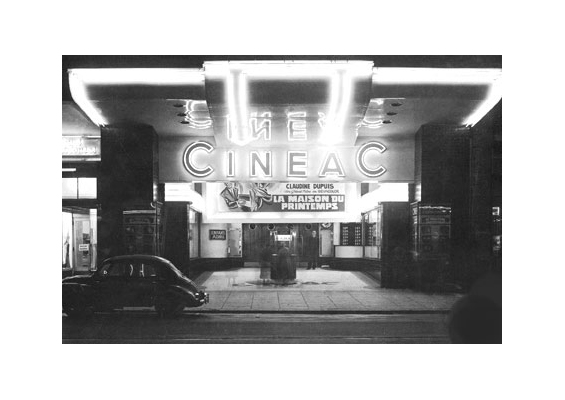

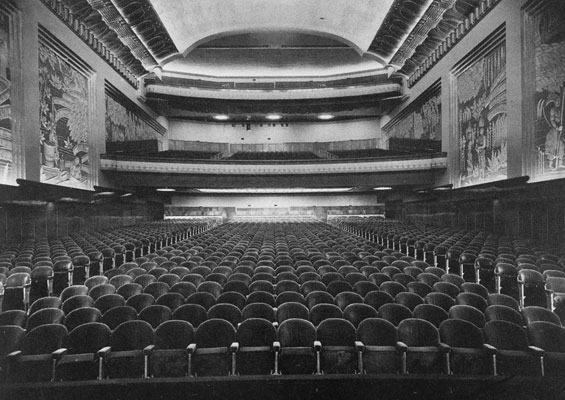

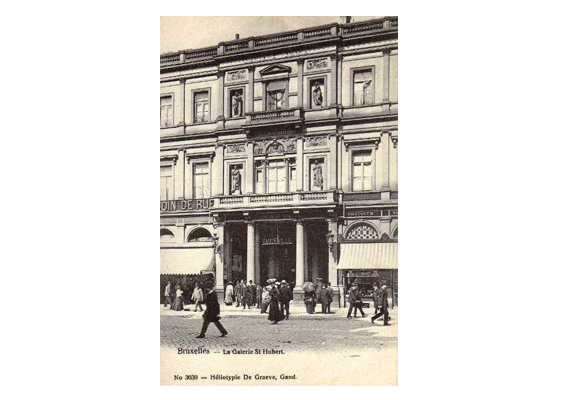

George Remi's mother, Elizabeth Remi, often took her son to the cinema, particularly during the years 1917 and 1918. It was the only distraction from the hardships of war. Among the establishments they visited were the Cinéma des Galeries, the same movie theatre in which the Lumière brothers screened their first movies in 1896.

By the time the future Hergé was watching films in the cinema, there were movie theatres all over the centre of Brussels. At the beginning of the 1920s the number grew from 23 to no less than 71 cinemas around the Bourse, Rue Neuve and the Place de Brouckère.

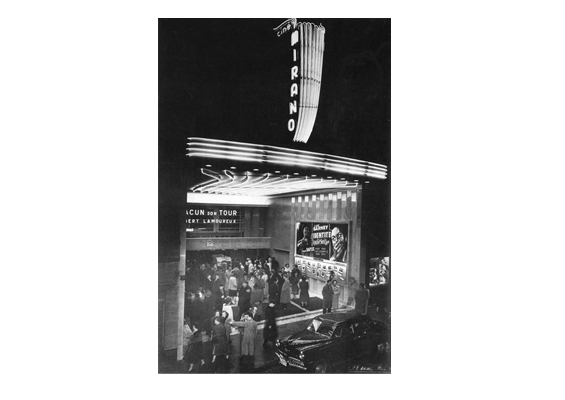

Following the spread of cinemas all the way up to the Gare du Nord (where theatres were often twinned with hotels), they sprang into existence around the Place Madou. The Grand Casino (which became the Mirano in 1934), for example, was founded on the Chaussée de Louvain. But what kind of films were these picture-houses screening? If you would like to see where these places are located, click on the Tintin.com link to 'Follow Tintin in Brussels'! But what kind of films were these picture-houses screening? It should be noted that, to begin with, films were often projected in large restaurants and dancehalls as temporary entertainment, before permanent projection galleries were set up. It was in some of these fledgling cinemas that Hergé discovered Charlie Chaplin, Harry Langdon, Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd. He would later come to admire Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy. And yet there were other films that made just as much of an impact on the young Hergé.

How do we know which films Hergé watched in his youth?

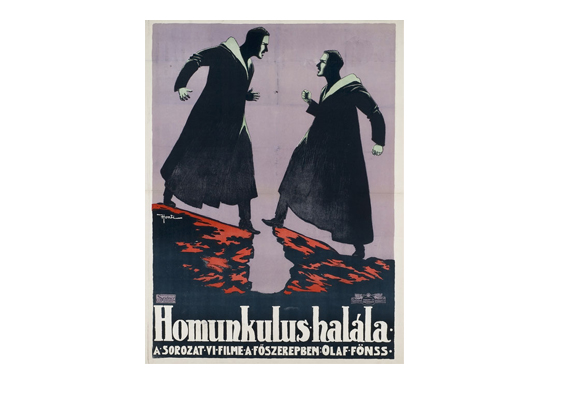

Hergé did not say much about the films that he saw in the cinema during his youth. The names of Chaplin, Keaton, Laurel and Hardy came up often in interviews that he gave to journalists. But while Elizabeth and Georges Remi, often went to the cinema, it should be noted that American comedy wasn't often on the menu! We know that Hergé often visited the cinéma des Galeries and the Excelsior in Etterbeek, the district of Brussels where his family lived. It also seems that he spent Thursday afternoons in a cinema in the Marolles, during visits to his grandmother who lived in the Rue Terre-Neuve. What do the listings for these cinemas tell us? In 1916 a German film, Homunculus, was on the menu. It is the story of a robot, created in a laboratory. His inventor loses his control over his invention and it becomes the master of the world in the midst of war!

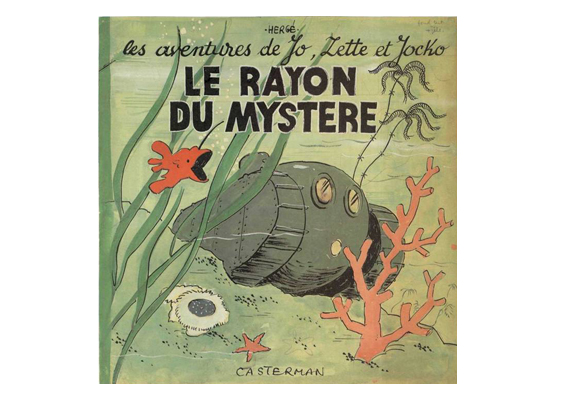

It looks like the maniacal machine and its creator inspired the mad professor in Hergé's story The Secret Ray (The Adventures of Jo, Zette and Jocko, 1935), as well as his robot.

Some forgotten films

We have forgotten it today, but back in the day Danish cinema was known all over the world during the first twenty years of the twentieth century. For example the film Forest Holger-Madsen, Les Spirites. This film was screened at the Cinéma des Galeries in 1917. The style of framing, and the lighting made an unmistakable impression on the future Hergé, who would evoke certain sequences in Tintin in the Land of the Soviets and Cigars of the Pharaoh (notably the dreamlike sequence inside the tomb of Pharaoh Kih-Oskh). Besides, Les spirites was well named: the film was full of special effects, linked to paranormal phenomenon.

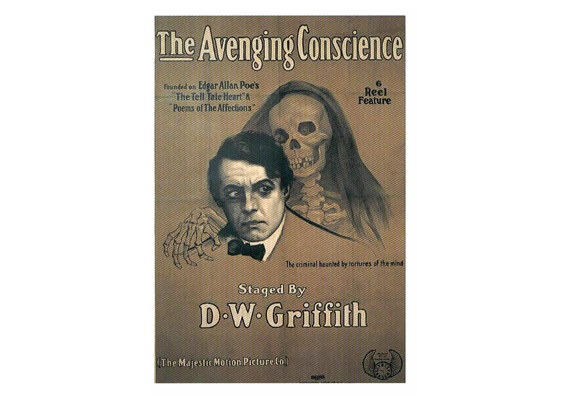

The Avenging Conscience (The vengeful conscience), by D.W. Griffith (1914, released in Belgium: 1919), is a 78-minute film with numerous nightmare sequences. One among them can be found, nearly image for image, in The Seven Crystal Balls.

In The Crab with the Golden Claws, we remember that in Tintin's bad dream, Captain Haddock wants to pull off his head with a corkscrew. A similar sequence can be found in The Avenging Conscience, but in this case it is a young criminal who wants to get an evil spirit out of his brain...

Did you know?

Fantômas was a big influence on Hergé. Fantômas, was a series of 32 novels that transfixed readers between 1909 and 1913. The invention of the authors, Pierre Souvestre and Marcel Allain, was genius: a criminal changes his face and identity to escape capture... like Rastapopoulos or Doctor J.W. Müller! Hergé did not read the novels but he did watch the movies adapted form the series - 5 silent films created by Frenchman Louis Feuillade (1873-1925). These 5 films: Fantômas (film, 1913), Juve contre Fantômas (film), Le Mort qui tue (film, 1913), Fantômas contre Fantômas (film), Le Faux Magistrat (film) were created in 1913 and 1914, and ran for more than 6 hours in total. Despite the German occupation, Brussels cinemas screened them during the 4 years of the First World War. This is where Hergé learned the importance of serialisation and suspense (see below).

Louis Feuillade inspired the baddies in Cigars of the Pharaoh. In 1916, the French director began work on his film Les Vampires. In twelve episodes, the viewers followed the exploits of a young journalist, Philippe Guérande, against a secret society, the members of which hid their faces behind hoods. This must strike a chord with readers of Cigars of the Pharaoh!

The French actor who played Philippe Guérande, Edouard Mathé, knew Hergé. Edouard Mathé (1886-1934) lived in Brussels for the last 10 years of his life. He was a fervent reader of Tintin. Mathé was a part of the events organised at the Gare du Nord train station in Brussels, to celebrate the return of Tintin from Russia, the Congo and America, in the 1930s. It was Mathé who suggested young scout Henri Dendoncker to play the role of Tintin retuned form the Congo. Mathé rented a flat in the same building as the Dendoncker family, in the Brussels district of Saint-Gilles.

Serialisation

Late in his life, Hergé remembered the serialised films that he saw in his childhood and teenage years. Today serialisations consist of separate episodes centred on a given theme, that can be watched separately. But in the 1920s super-long films were simply chopped into several episodes. The Three Musketeers was serialised and screened over several weeks. In the United States, The Adventures of Superman was spread out over months, and was only interrupted when audience numbers began to go down. This type of cinema was the direct descendant of serialised novels, popular from the 1830s until the 1950s, when they became almost extinct. And this was all before the television soap operas we know and love today! The first films were shaped by technological constraints: silent films showed images interspersed with written text that explained action or indicated essential dialogue.

The big question!

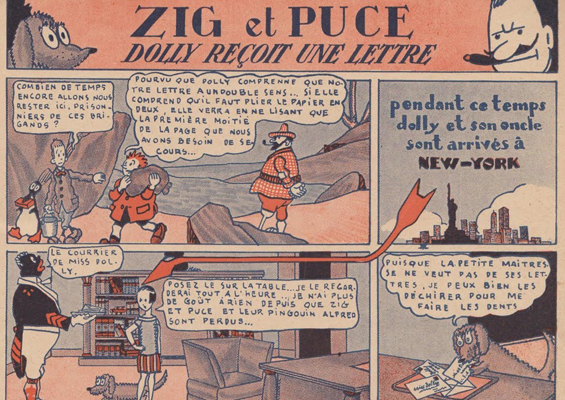

Episodes often had to close with a cliffhanger or some kind of inextricable situation. Hergé clearly remembered these endings. Not only would he integrate these fundamental principals into his stories, but he also insisted that authors published in Tintin magazine (from 1946) also respect the principles. It should be remembered that Hergé, Frenchman Alain Saint-Ogan, creator of Zig and Puce, had adopted the technique of serialisation, inspired by the United States, while remaining faithful to the idea of one-page weekly gags. In this way occasional readers were not put off.

Tintin's first adventures (Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, Tintin in the Congo, Tintin in America), also show signs of being cut into a series of weekly gags and episodes. These days manga comics are created with the same idea in mind and along the same codes of creation: each weekly issue (of 20 pages) has to have a shock image, a certain number of exciting happenings, the expression of a certain number of expressions to clearly define the characters and, last but not least, suspense at the end of each episode.

News

News Forums

Forums E-books

E-books