3D: the inside picture

Is 3D the future of cinema? Perhaps! But it is also the past of cinema, because ever since films were invented attempts have been made to incorporate three dimensions, some more successful than others, without any technique really becoming a runaway success. What about current experiments to plunge audiences into the world of film? We look forward to finding out how far 3D has developed in Tintin, coming to a cinema near you in 2011.

Avatar adds a new dimension

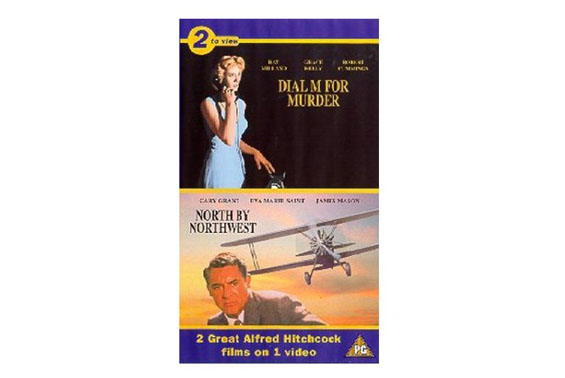

3D has been eagerly awaited by film fans. Since its release on 18 December, Avatar, the latest film by James Cameron (director of the hugely successful Titanic), and a movie which can be seen in 3D, has grossed over $1.3 billion worldwide. Presented as something that will revamp cinema, does 3D represent its future? This is certainly possible, as long as the subject matter is interesting and the plotlines remain solid. It is easy to forget that the late great Alfred Hitchcock created two of his major thrillers in 3D: Dial M for Murder (1954) and North by Northwest (1959). These films are still shown at cinemas and on television today, but not in three dimensions! The ‘master of suspense’ was not the first to choose 3D for his films: the history of three-dimensional entertainment goes back a long way…

Back to the origins of 3D… and history!

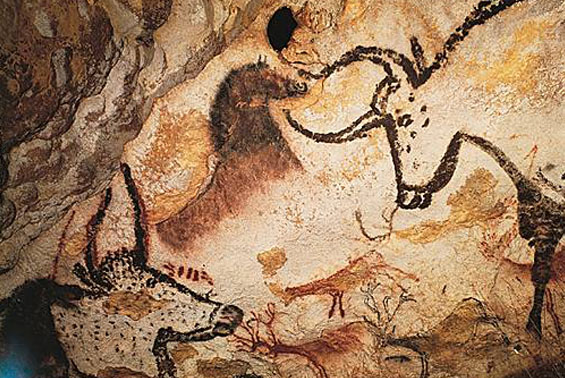

Seeing the world in three dimensions all comes down to having two eyes. Each eye sees a slightly different image. The two images are sent to the brain, which analyses both of them and process them as stereoscopic (three-dimensional) vision. This allows us to gauge the volume of objects observed and also to judge how near or far they are from our eyes. When our earliest ancestors started to portray scenes of daily life, notably hunting scenes, they were already looking for ways of representing the volume of animals. To create the effect, they made use of protuberances, nooks and crannies on the surface of rocky walls, and drew animals around these bumps, thus giving them a certain volume. The use of natural rock formations in this way is clearly visible in the rock paintings discovered around 1950 in the region of Cape Town in South Africa.

The cornerstone of 3D

Sculpture, an art form using diverse materials such as wood, stone and terra cotta, was born from the desire to portray living beings and objects while rendering them as accurately as possible in relation to their proportions, volumes and features. This is what it means to be three-dimensional! Painting is also concerned with distances and volumes. The classic example is the school of art known as trompe-l’oeil: pictures giving false impressions of the proportions of a room, or the impression of life-like realism. Many Baroque-style interiors of Jesuit churches in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries employ trompe-l’oeils to create the illusion of extra room height often making ‘space’ for heavenly scenes. All things considered, 3D cinema is a kind of trompe-l’œil: an image is projected onto a screen, although it appears in three dimensions. To arrive at this point, a process of several stages has to be completed… and of course the cinema needs to have been invented in the first place. Although a handful of inventors had managed to create various moving images before them, French brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière are credited as the first inventors of the cinema as a mass medium, with their first public screening in Paris in December 1895. We won’t get into the debate about the date of the first animated film: the English, Italians, Americans, Germans and even New Zealanders are vying for first place!

The fascination for three-dimensional images

From the eighteenth century, various inventions, which gave rudimentary three-dimensional effects, were created as distractions for the court of Louis XV, as well as in Prussia, Austria and Russia. We were still, however, a long way off from what we today understand as stereoscopic images. The first major difference is that these 3D images were not projected onto a screen or any other surface: the effect was achieved by looking into a candle-lit box via two holes. The box contained static scenes often portraying characters and scenery cut-outs fixed at different distances, as if on a miniature theatre stage. Contraptions called ‘viewers’ were accordion-like structures which were stretched out before the eyes in order to admire exotic landscapes, compositions based on the novels of Jules Verne, etc. But it seems that the first true stereoscopic image dates from 1838, and was created in France. In reality, two slightly different images are brought together in one viewer; the eyes see the images and the brain processes them to create the illusion of three dimensions.

The View Master odyssey

In 1939 a church organ builder called William Gruber, and Harold Graves, an employee of the photographic firm Sawyer’s, combined their efforts to perfect a camera which could take three-dimensional pictures. The principle was again based on the miracle of our two eyes: the same subject was photographed twice from very slightly different angles. Once the pictures had been taken, the transparent photographs were inserted into a disk which contained 14 photos arranged in 7 pairs. The disk was slipped into a viewer which scrolled through the images. The content was very varied: landscapes, holiday souvenirs (notably national parks and treasures, animals, exotic scenes, etc.) and adaptations from cartoons and films. Even Tintin graced the View Master with extracts from his lunar adventure.

The first films in 3D

Specialists arbitrarily place the projection of the first 3D film in 1903. In that year, the Lumière brothers screened their film The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station to the Parisian public, who thought that a real train was pulling into the cinema! In fact it wasn’t really a 3D film: the spectators were simply astounded by the train bearing down on them thanks to the use of a clever camera angle. The first films in 3D were produced for sheer entertainment value as opposed to being serious films. The most popular method consisted of superimposing two images – one red and one green – onto a film reel. The spectator wore glasses of which one lens was red (and cancelled out the red image for the left eye, which could then only see in green) and the other was green (which cancelled out the green image for the right eye, which could then only see in red). Three dimensions were thus created, but the process could only be applied to black and white film.

The golden years – the 1950s

The first 3D film to be a genuine public success was screened in 1952, but who can remember its title (Bwana Devil !) let alone the plot? The three-dimensional effect was used to enhance images popular to the older methods of stereoscopic vision: herds of elephants charging at the viewers, angry lions leaping forth, etc. Alfred Hitchcock considered 3D to have potential (see above). John Wayne starred in Hondo, a 3D western. These films, more developed than their predecessors, required heavy equipment: two projectors had to be closely synchronised; spectators wore polarised glasses that created the 3D effect and added some of the colour. Films such as Jaws 3 and Friday the 13th Part III were screened in 3D. In 1970, the first IMAX film, Tiger Child, was screened at Expo ’70 in Osaka, Japan. Since then, IMAX has achieved a certain success and recently a number of Hollywood blockbusters have been released in IMAX cinemas, including the Matrix sequels and Harry Potter. Today, 3D cinema is going through a revival thanks to developments in digital photography: Avatar is the latest demonstration of this renewed interest.

What does the future hold: new heights or the Super-Calcacolor?

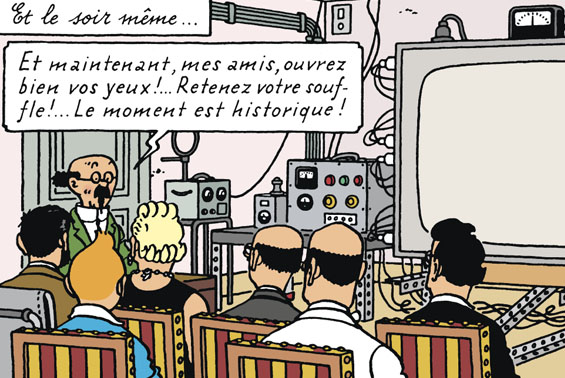

The success of Avatar has reinvigorated old projects which have been kept on ice in the research centres of the big names in television manufacturing: Panasonic, Samsung and Sony. In Las Vegas from 7 to 10 January, visitors to the Consumer Electronics Show (C.E.S.) – the famous annual exhibition for fans of all kinds of electronic appliances and gadgets – were able to admire prototypes demonstrating what the near future may look like from the comfort of our living rooms. But the big question is, does 3D have what it takes to become a long-term success, or is it just a flash in the pan? Considering all the previous failed attempts to definitively introduce the format to the public, will this latest phase in 3D ultimately be successful? It is too early to say. Nobody can guess whether it will catch on or whether the public will get sick of it, just as readers of The Castafiore Emerald got a headache from the Super-Calcacolor, one of Professor Calculus’ inventions that never took off.

3D is OK, but what about the catalogue?

Since the first stereoscopic projection in 1903, up to the present day, some 300 3D films and television programmes have been screened at cinemas and at home. Once the novelty has worn off, viewers have shown themselves to be pretty dismissive of three-dimensional cinema. The main reason for this lack of enthusiasm is the poor catalogue available to viewers. Most films shot in 3D have tried to play on the audience’s sense of vertigo, anxiety, awe, etc., with plotlines usually playing second fiddle to these mind-bending illusions. Nevertheless, with film speeds of 64 frames per second against the normal 24 frames per second, and giant screens on which to project movies, IMAX cinemas have a fairly interesting, albeit relatively small list of titles (mainly documentaries). IMAX does have problems, however, including the fact that the format requires special rooms, screens and projection equipment, and the fact that the 3D effect can’t be reproduced on DVDs, unless they are all accompanied by fiddly 3D specs. To win the hearts of cinema fans everywhere, 3D has teamed up with Tintin. In October 2011, The Adventures of Tintin: The Secret of the Unicorn, the film by Steven Spielberg and Peter Jackson based on The Secret of the Unicorn, Red Rackham’s Treasure and The Crab with the Golden Claws, will hit the big screens. The three-dimensional experience will complete the special effects currently being added to the performance-capture action already filmed, about which we have already made a report. We will keep you posted on events as they happen!

News

News Forums

Forums E-books

E-books