Tintin and Alph-Art

Left unfinished when he died in 1983, Hergé's last episode, Tintin and Alph-Art (published in 1986), was to describe the occult world of sects. It was also going to send Tintin wandering into a milieu that Hergé loved, that is the world of modern art and avant-garde. Although the posthumous album is only presenting the scenario and sketches of an interrupted tale, it is however the testimony of the extraordinary narrative and graphic talent of Tintin's father. Just like Tintin, just like the story, we, the readers, will remain magically suspended to Hergé's quill.

Test your knowledge

+

Tintin’s last adventure...

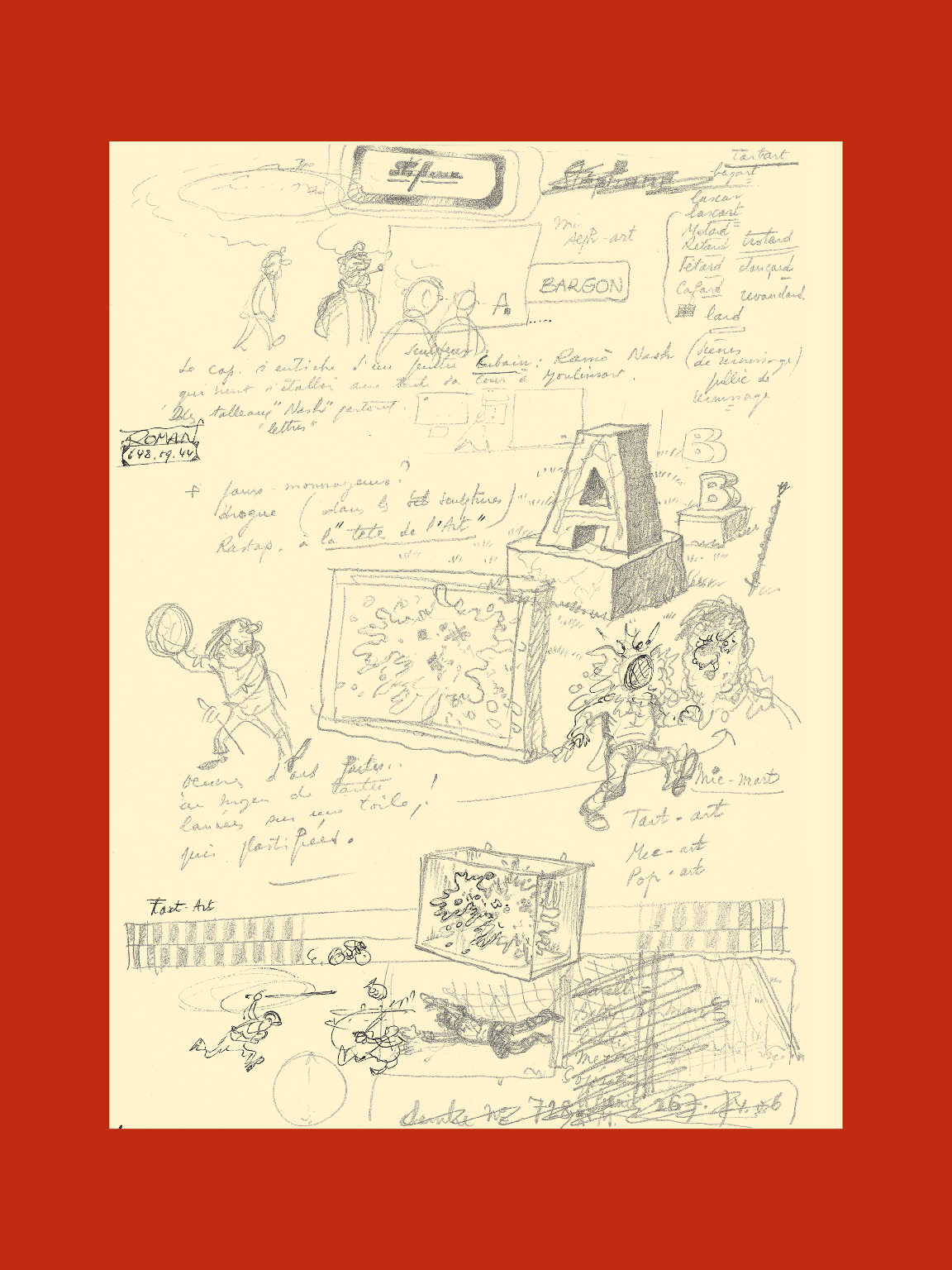

The twenty-fourth and final title in the Tintin series is an unfinished symphony. Three pencilled page, forty-two further pages roughly sketched, a few pages of storyline, and other scribbles and notes, make up Hergé’s ultimate story. There is clearly enough material for a very promising adventure, although the work is somewhat fragmented.

Art or not art: that is the question

Hergé chose the contemporary phenomenon of religious sects, with their gurus and disciples, as an element to weave into his storyline. The plot unfolds against the backdrop of the modern art world, which Hergé knew well.

The creator of Tintin was extremely interested in modern art, and spent a lot of his spare time visiting galleries and exhibitions. Hergé even tried his hand at creating his own modern art, although he thought that the results were not very promising. He decided not to take his hobby further and instead consecrated his spare time to his passion for collecting.

The adventure begins

Captain Haddock, following the advice of Bianca Castafiore, buys a work of art – a Perspex H – by Ramo Nash, the creator of Alph-Art. A short while afterwards the owner of an art gallery, Mr Fourcart, is assassinated. Tintin sets out to solve the case.

“Truth and lies”

It is very likely that Hergé saw the Orson Welles film F for Fake, which hit the big screen in 1974. The film – created in mock-documentary style – portrays the life and work of the notorious Hungarian forger Elmyr de Hory. Orson Welles spun an intricate web of truth and deception to create a movie that has since been hailed for its visionary editing techniques.

Alph-Art: H for Hergé...

Alph-Art is an imaginary artistic movement founded by forger Ramo Nash, who paints and sculpts the letters of the alphabet. The high priest of Alph-Art shows off a capital A and a capital Z, which stand for, in Bianca Castafiore’s words, ‘a microcosm of the whole universe’.

Endaddine Akass

Bianca Castafiore succumbs to the charm and charisma of this undesirable character. She gushes, ‘He is a fascinating man, darling, absolutely fascinating. You simply must meet him. He's the most m-a-a-rvellous mystic... He lays his hands on your head and you're magnetised for a year.’ It is worth noting that in his choice of name, Hergé was up to his old tricks: “En dat in â kass” in Brussels dialect could roughly be translated as “take that in the face”!

Endaddine Akass runs a network of forgers; he is also a guru and the host of the Health and Magnetism spiritual teachings. Physically he resembles Fernand Legros, a forger who was active at the time the story was written.

The Fourcart Gallery

One of Hergé’s friends, Marcel Stal, was the director of the Carrefour Gallery in Brussel. Stal provided some of the inspiration for the character of Henri FOURCART, director of the gallery named after him.

The Pompidou refinery

In a television interview, Emir Ben Kalish Ezab amusingly and unwittingly expresses the feelings of many French people and visitors to France, when he speaks about the Beaubourg Centre: ‘a refinery turned into a museum’!

The official name of the building is the “Centre National d’Art et de Culture Georges Pompidou”, and it was created between 1971 and 1976 by Italian architect Renzo Piano and Englishman Richard Rogers.

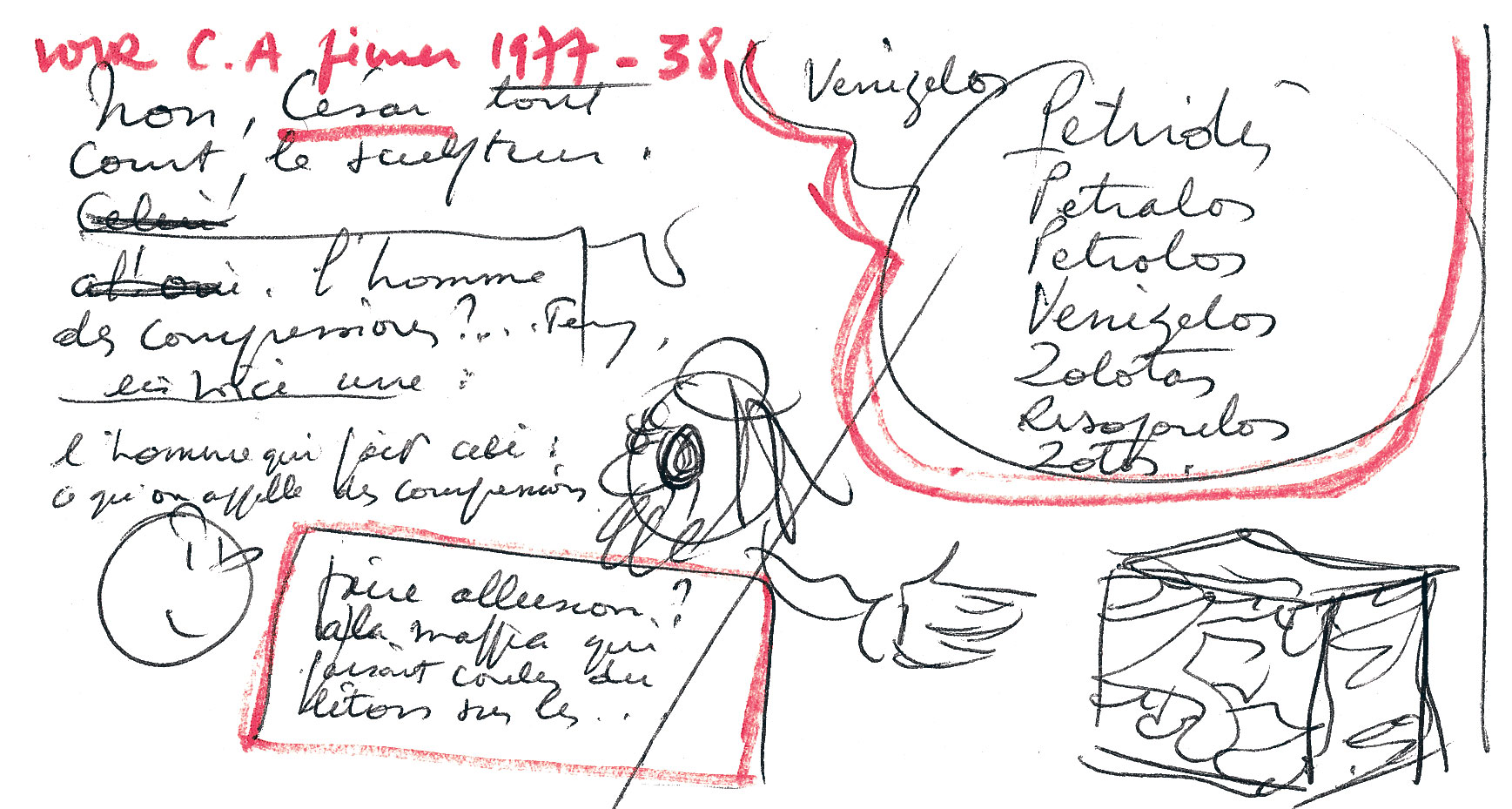

A César sculpture

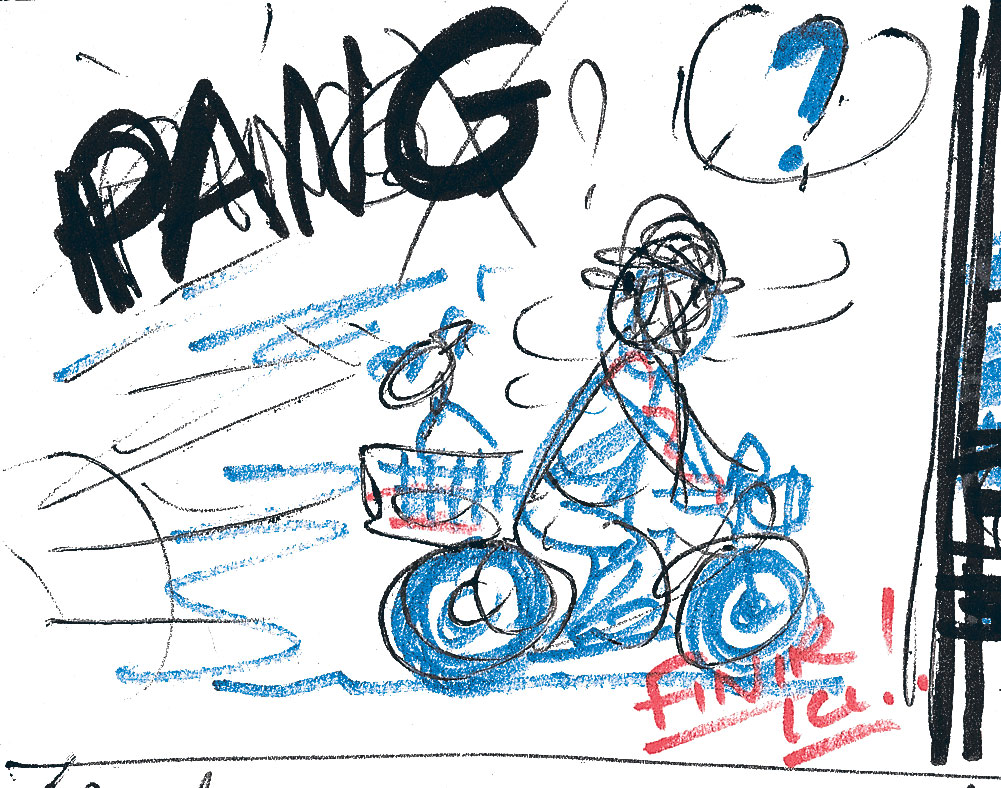

Endaddine Akass has a particularly nasty end planned for Tintin: to get rid of him by turning him into a fake work by sculptor César.

César Baldaccini, a French artist whose ‘Compressions’ of cars (1960) and ‘Expansions’ of plastics (1967) earned him fame and fortune. Smaller works by César have been awarded to outstanding achievers in the French film industry since 1975.

The death of a hero

Is Tintin fated to share the outcome of famous British amateur detective Sherlock Holmes, whose creator Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930) ended Holmes’ career in 1927?